Have you ever stopped to ponder the connection between your wardrobe and your house? On the surface, they may seem worlds apart, but in truth, they share a profound similarity – both serve as protective shells against the elements, offer comfort, and act as canvases to express our unique identities and personalities. Yet, the historical bond between fashion and architecture was somewhat limited, primarily due to the stark contrast in materials employed. However, in the age of technological innovation, especially with the advent of 3D printing, the once-clear boundaries between building and attire are blurring. In this era of techno-evolution, the parametric style emerges as a rising star in the world of design.

But what exactly is parametric? In the realm of mathematics, a parametric equation establishes a set of quantities as functions reliant on one or more autonomous variables known as parameters. However, in the field of architecture, this concept takes on a different context. Parametricism is a contemporary avant-garde architectural style that has been advocated as a replacement for Modern and Postmodern architectural approaches. This term was introduced in 2008 by Patrik Schumacher, an architectural collaborator of Zaha Hadid (1950–2016). The foundation of Parametricism lies in parametric design, which is rooted in the constraints found within parametric equations. This architectural style heavily relies on the utilization of programs, algorithms, and computer technology to manipulate equations for the purpose of designing structures.

Picture this: the world of computer programming and visualization soaring to unprecedented heights, all thanks to the remarkable capabilities of advanced 3D printing machines. These modern marvels aren’t limited by material; they can craft in concrete, fabric, plastic, or even eco-friendly substances. In this age of cutting-edge technology, the parametric style is pushing the boundaries of experimentation like never before.

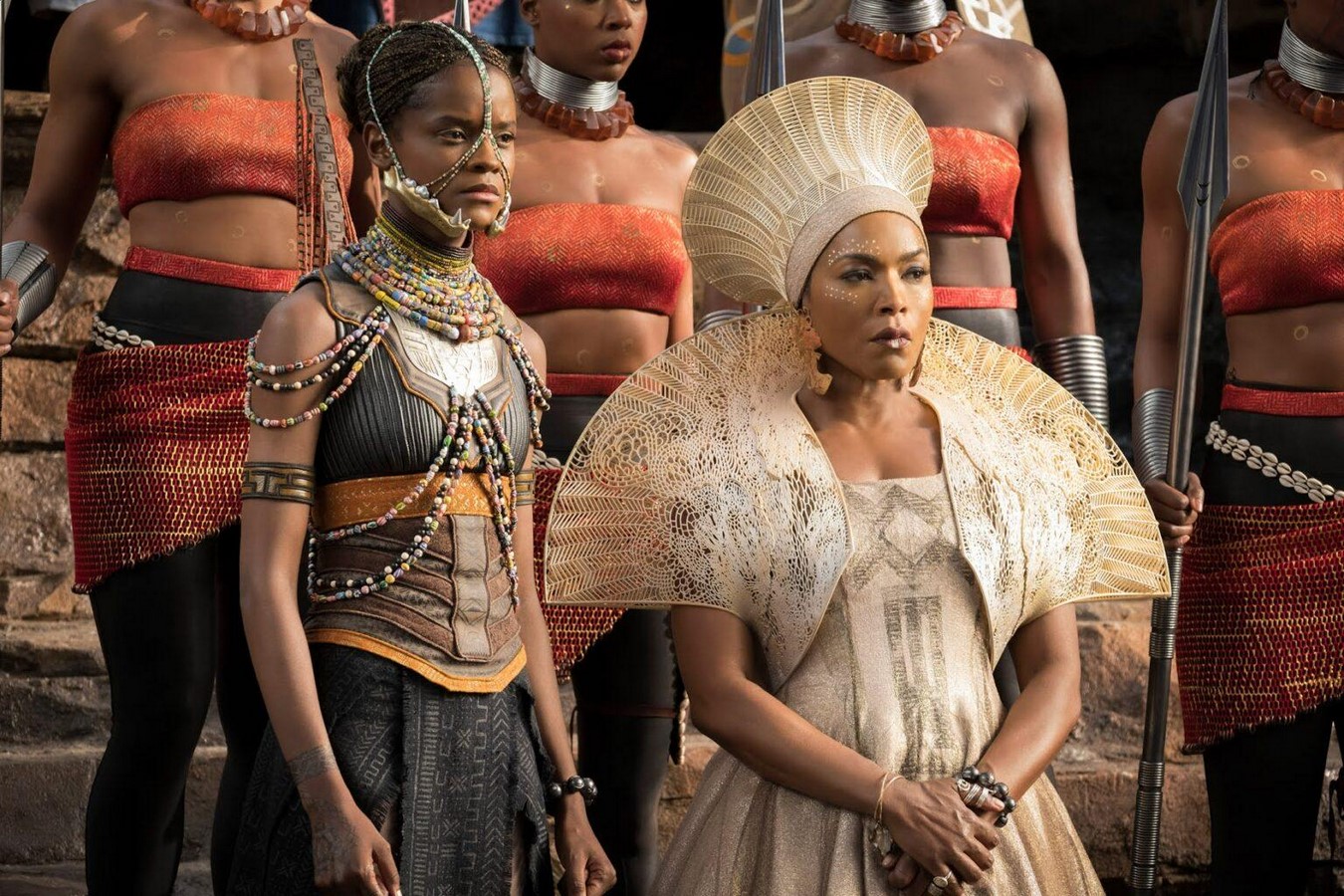

But here’s where it gets truly exciting: Designers are turning to architecture for inspiration and infusing their fashion sketches with the intricate patterns found on building facades. Imagine wearing a piece of art that embodies the very essence of architectural symbolism. It’s not just clothing; it’s an extension of one’s identity, taking the fusion of fashion and architecture to a whole new level. Architecture, once confined to concrete and steel, is now becoming an integral part of personal style through fashion.

One of the example of fusion of fashion and architecture can be seen in Muslim clothing, where middle eastern designer used inspiration of geometrical shaped ubiquitous in Islamic architecture into clothing design. Numerous contemporary designers of Islamic patterns use traditional techniques rooted in sub-grids of polygons, often referred to as “touch polygons.” Stars, in particular, served as convenient placeholders for motifs in these designs. This approach involved creating a star polygon by connecting each corner in every direction. The starting point was to discover that a star could serve as a stand-in for any of the three renowned Islamic star patterns: stars, rosettes, and extended rosettes, as described by Webster (P).

For a more contemporary and versatile look, there are a few designers pioneering the use of 3D printing. Iris van Harper, a Dutch designer, is among the first to embrace 3D printing in the fashion industry. She creates impressive clothing worn by numerous celebrities at significant events such as the Met Gala and Paris Fashion Week. Furthermore, she has collaborated with the Belgian brand Magnum to unveil a haute couture dress created through 3D printing. This dress is made from vegan organic materials derived from cocoa bean shells. Her work exemplifies the intersection of fashion, design, technology, science, and nature, serving as a testament that nature, fashion, and technology can be combined through unconventional techniques.

Another example of a modern designer combining design, technology, and sustainability is ZER Collection from Spain. The founders have initiated a research project focused on achieving zero waste production. In addition to being biodegradable, these fabrics also adhere to a closed life cycle. The utilization of 3D printing technology holds the potential to further enhance the sustainability of the entire fashion industry. Thanks to this technology, ZER Collection can digitize all patterns, ensuring that production utilizes only the necessary amount of fabric. Typically, during the cutting process of most apparel, up to 30% of the fabric becomes waste. By employing 3D printing technology, they employ precise measurements for each garment, drastically reducing waste to nearly zero.

Their entire production process, from design to final use, revolves around sustainability. ZER Collection also embraces recycling by repurposing materials from used garments. Plastics are melted down to create printable filaments, which are then reused in crafting new items, closing the loop on sustainability.

In conclusion, the intersection of fashion and architecture represents not only a stylistic evolution but a profound shift in the way we conceive of the spaces we inhabit and the clothes we wear. Parametric style, with its roots in mathematics and its applications in both architecture and fashion, is reshaping our creative landscape. It serves as a testament to the boundless possibilities that emerge when technology, design, and sustainability converge. Fashion and architecture are no longer solitary entities; they are becoming intertwined threads in the fabric of our innovative future.

References:

- Schumacher, P. (2010, May 6). “Patrik Schumacher on Parametricism – ‘Let the Style Wars Begin’.” Architect’s Journal. Retrieved from https://www.architectsjournal.co.uk/practice/culture/patrik-schumacher-on-parametricism-let-the-style-wars-begin

- Jabi, W. (2013). “Parametric Design for Architecture.” Laurence King. ISBN 9781780673141.

- Frazer, J. (2016). “Parametric Computation: History and Future.” Architectural Design, 86 (March/April), 18–23. doi:10.1002/ad.2019. S2CID 63435340.

- P., A. (2022, August 4). “3D Printed Fashion: The Top Designs.” Retrieved from https://www.3dnatives.com/en/3d-printing-fashion-designs150620174/#!

- N41. (2021, May 28). “The Rise of 3D Printing in Fashion.” Retrieved from https://www.n41.com/the-rise-of-3d-printing-in-fashion/

- Team Editor. (2021, April 22). “Must-Know 3D Printed Clothing Designers.” Hybrid Rituals. Retrieved from https://hybrid-rituals.com/must-know-3d-printed-clothing-designers/

Citation :

- Architecture 2030. (n.d.). “Why the Built Environment?” Retrieved from https://architecture2030.org/why-the-built-environment/

- Here’s the Harvard style citation for the provided link:

- Brodka, C. (2023, August 23). “Re-Wilding in Architecture: Concepts, Applications, and Examples.” ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/1005791/re-wilding-in-architecture-concepts-applications-and-examples

- Ghisleni, C. (2023, January 12). “Architecture as Collaboration Between Human and Non-Human Species.” ArchDaily. Retrieved from https://www.archdaily.com/994659/architecture-as-collaboration-between-human-and-non-human-species?ad_medium=widget&ad_name=related-article&ad_content=1005791

- Chakraborty, R. (2022). “Eastgate Centre: Green Architecture Innovation Type Enterprise Venture.” City2City Network. Retrieved from https://city2city.network/eastgate-centre-green-architecture-innovation-type-enterprise-venture