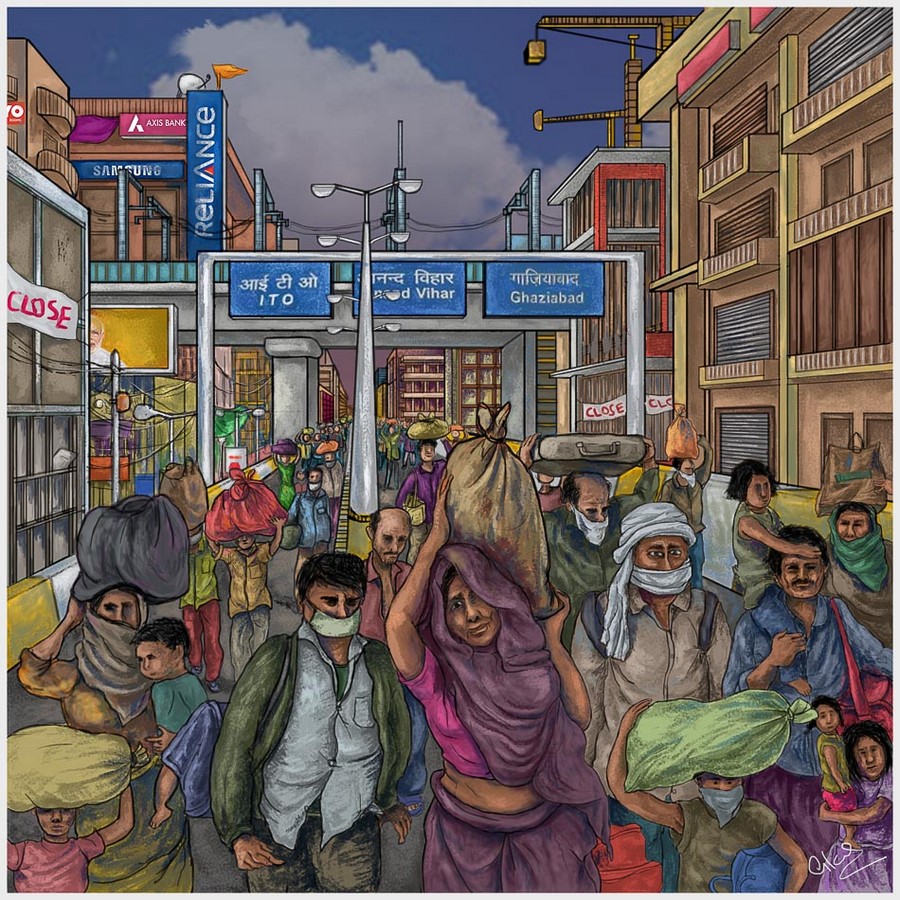

It is believed that pandemics throughout history have played an important role in shaping our cities. Today, when the world is fighting against the COVID-19 public health crisis, Indian cities are facing many challenges and inadequacies to face this pandemic. Many have blamed rapid urbanization for the failure of providing even basic amenities to the most vulnerable communities.

It is no doubt that the pandemic has raised many questions about the spatial planning of our cities, access to public health infrastructure, and the impact of physical surroundings on one’s mental health.

The COVID 19 crisis has urged everyone to re-envision our cities. We, as practitioners, need to promote new kinds of architectural and planning practices that focus on integrating public health practices, social thinking, improving our natural systems, and protecting humans from calamities.

Historical Transformation of Cities Post Pandemics

Like COVID 19, many pandemics have hit the world and ended the lives of millions, while having a long-lasting urban impact and economic consequences. For example, the black death crisis enabled the design of large public spaces in European cities for people to connect with nature and reduce the feeling of isolation. (Eltarabily S. & Elghezanwy D., 2020)

Similarly, in Bombay, it was in the late 1890s after the plague that Bombay Improvement Trust (BIT) was set up to provide sanitary accommodation for the working class. It is believed that it was only after the “horrors of the plague” that the colonial State intervened in the poor housing conditions of the city. It was established that ‘light and air—nature’s two great healing elements’ were the solution for unsanitary living conditions. (Indorewala H. & Wagh S., 2020)

Strict building by-laws (housing densities, set back rules, plot area and coverage, and height restrictions) were set up to ensure adequate light and ventilation in all rooms of the building. In 2021, it is time to learn new lessons from the COVID 19 pandemic instead of accelerating current urban trends that have led to designing ‘divided cities’.

Towards building equitable cities

The pandemic’s disastrous impact on the cities of India has underlined the importance of urban planning and development that is integrated, inclusive, and resilient. It is understood that a city’s ability to deal with the scale and severity of a crisis like COVID 19 highly depends on its control over decision-making and planning systems, the quality of public infrastructure, and accessibility of services.

In India post-liberalization, however, we have handed over the responsibility to the private sector to determine all the aspects of urban life, including housing, health, and transport. The State, which was supposed to regulate the activities of the private sector to ensure public good in turn, became a promoter of ‘urban development projects.

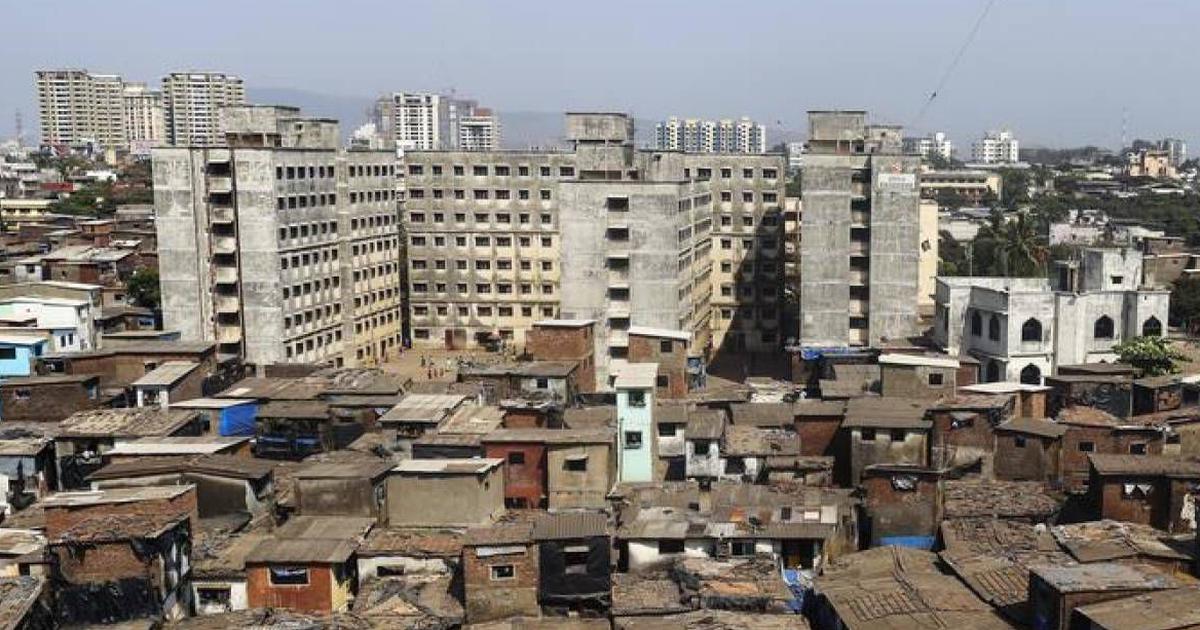

For example, Mumbai’s slum redevelopment projects in the hands of private developers have led to the building of tightly packed high-rises with inadequate access to light, ventilation, and services with deplorable living conditions. Such policies have not only contributed to the inequality that exists in our society in terms of living conditions/access to services but has also weakened our ability to prepare and respond to a crisis.

It is high time to take control back in the hands of collective public planning systems with a focus on public health, food distribution, public housing and transport, sustainable practices and climate action plans to prepare against disasters in the future.

Housing for one and all

The “Housing for one and all” model should become the agenda for our nation. The State should play a proactive role in providing housing for the poor instead of facilitating mega-real estate projects. It is important to maintain the basic quality of life across all income groups by considering several aspects including building typology, common services relating to energy, water, and waste, locational aspects, connectivity, and resource efficiency. (Adlakha N., 2020)

Housing thus, cannot be looked at in isolation from livelihoods, amenities and public realm, transport, and services. From the view of public health, we need to relook at the current trend of organizing high densities in high rises that look like tiny boxes in the sky. Such building typologies often create an environment for disease transmission.

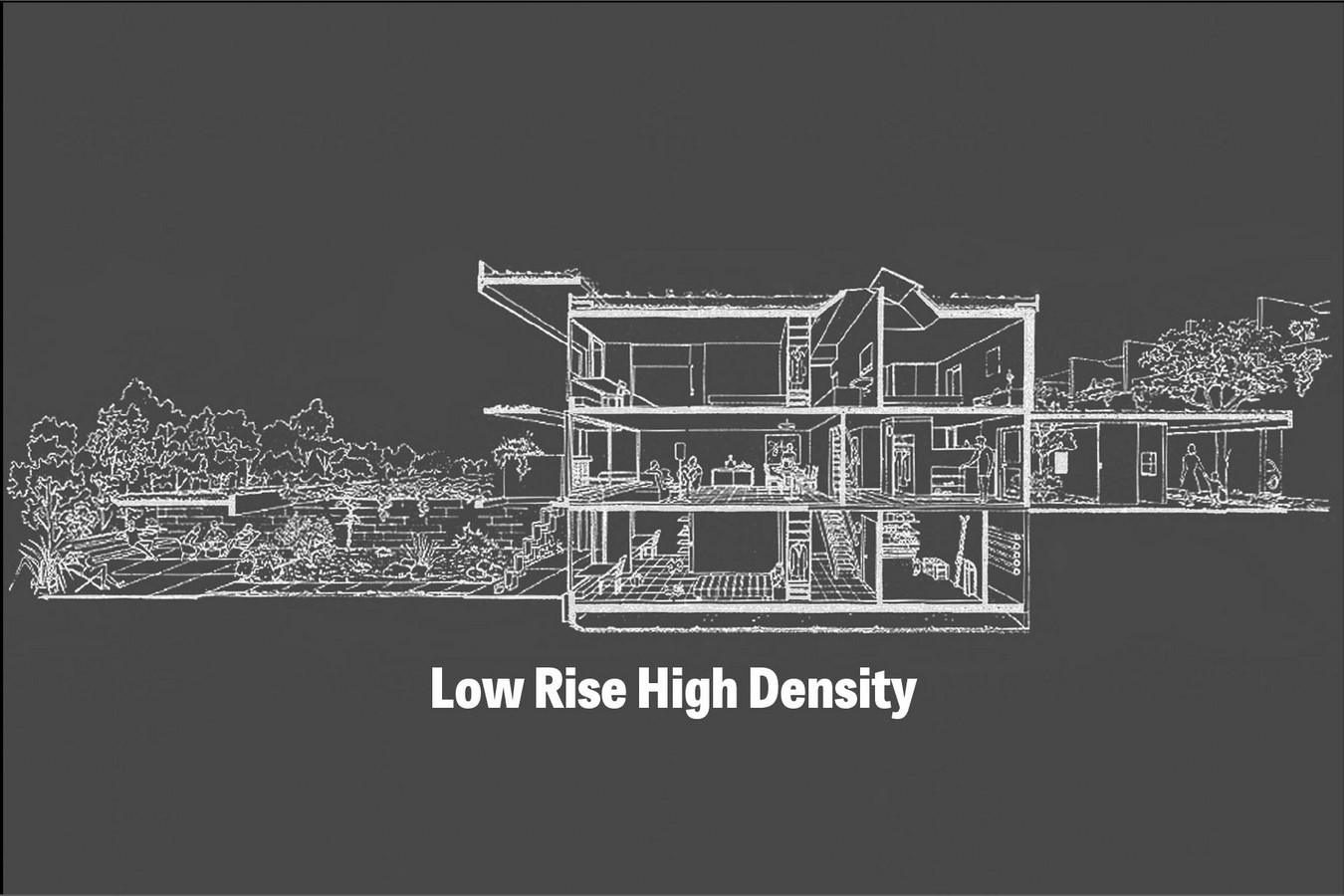

We should consider low rise alternatives with larger open spaces, with comprehensive guidelines for materials and architectural design to incorporate ideas of energy-saving, optimizing access to sunlight and wind, reducing the need for air conditioning, integrating green spaces and creating a micro-climate, mutual shading of buildings to reduce heat island effect, etc.

Proposals for spatial planning

The ‘model has proved to create a safe, active, and thriving environment and is less impacted during the restrictions of the pandemic. It not only allows the community to support each other but also ensures that the vulnerable communities get access to services and do not remain neglected during the crisis. It is obvious that areas with dense urban poor populations, often ghettos, were highly impacted due to the pandemic.

Owing to lack of infrastructure and amenities, such as adequate access to electricity, water, toilets, drains, streetlights, spaces for recreation/education, on top of dwindling livelihoods, these marginalized communities were the worst hit. By moving towards mixed neighborhoods, spaces for work and life can co-exist such that people do not have to travel long distances in search of job opportunities.

Mixing income groups might best address our goals of poverty alleviation and social equity. It can also create a community-based living with a focus on small public parks/open spaces, streets with wide pavements, shared community spaces, and decentralized public spaces to encourage a safe and healthy lifestyle.

As we can see, it is the need of time to look at the ‘future of architecture/ urban development’ in the light of ‘holistic development’. It is essential to understand the role that physical development plays in achieving human development goals and social welfare and equity, and act on it responsibly.

References

[1] – Eltarabily S. & Elghezanwy D. (2020). Post-Pandemic Cities – The Impact of COVID-19 on Cities and Urban Design. Available at: http://article.sapub.org/10.5923.j.arch.20201003.02.html

[2] – Indorewala H. & Wagh S. (2020). After the pandemic, will we rethink how we plan cities?. The Wire. Available at: https://thewire.in/urban/city-planning-pandemic

[3] – Adlakha N. (2020). Urban Planning for the Post-Pandemic World. The Hindu. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/real-estate/urban-planning-for-the-post-pandemic-world/article31473376.ece