Prison Architecture

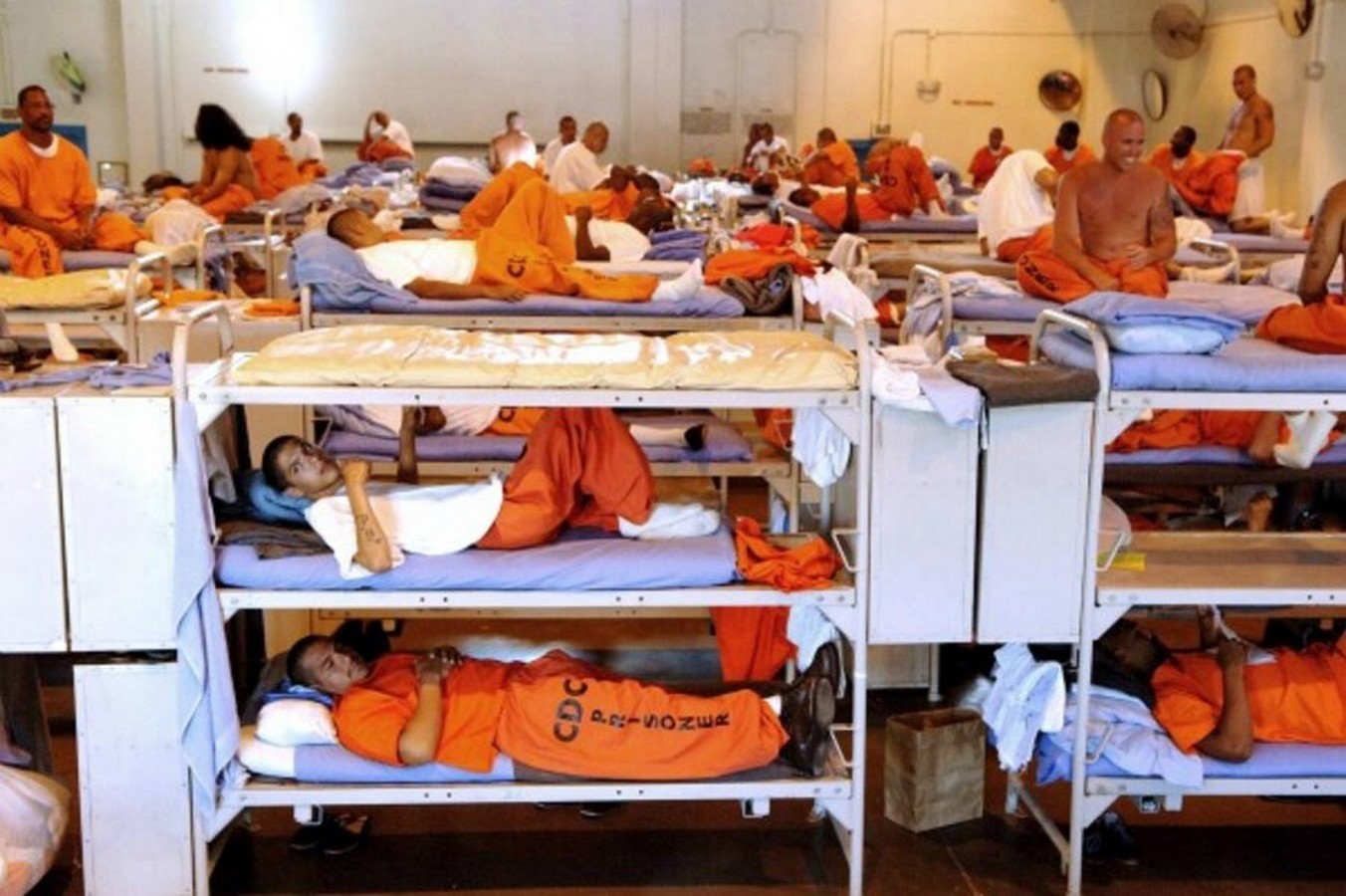

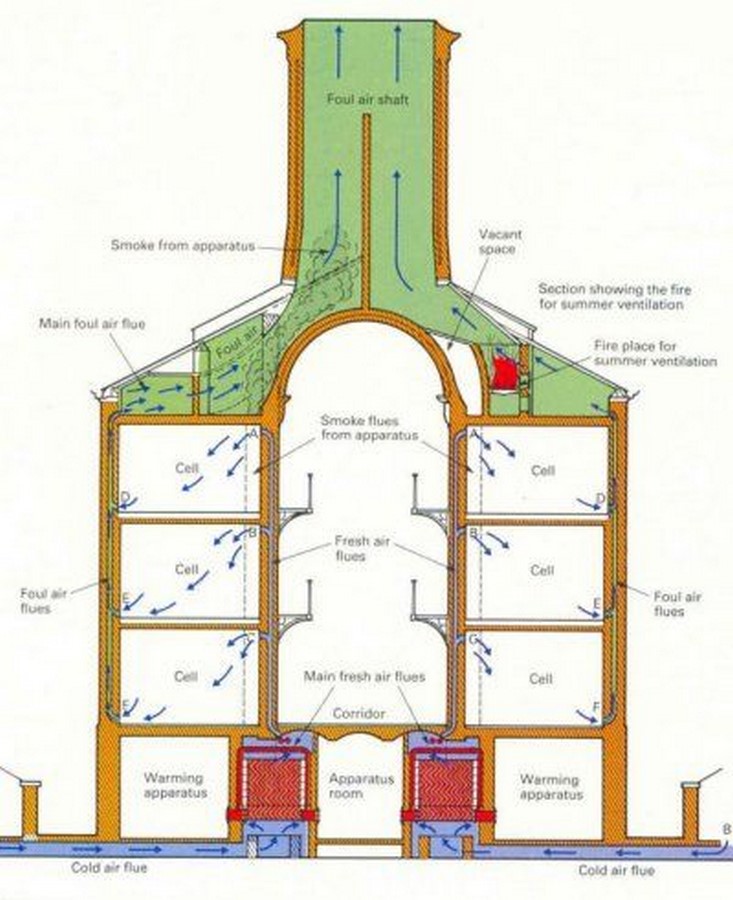

Prison facilities house hundreds of inmates in tiered blocks of single- and double-occupancy cells, some even five levels high. Some have practically no solid walls or floors between them and barred doors exposed to exterior walkways. These spaces share air with little or no ventilation. The eight have no windows completely, or the existing ones have been welded shut. These are prime conditions for a respiratory pathogen to spread.

Architecture plays an important role in the site selection and operations of incarceration facilities.

Issues that are tolerable to regular people are magnified by incarceration as inmates do not have the option to just up and leave when uncomfortable; even small irritants become major stressors over time.

The wardens and guards spend just as much time in prisons as the inmates, and their welfare needs to be taken into account when designing prisons.

The body’s biological clock, the circadian rhythm, is controlled by exposure to sunlight. In most prison setups, access to daylight is limited by restrictive architecture and regimens.

Being in contact with nature is critical to human mental and physical health. The biophilia hypothesis assumes there is a survival advantage gained from direct contact with nature. Multiple studies suggest that exposure to nature reduces stress and that there is an evolutionary advantage conferred by rapid stress recovery.

Prisons and Pandemic

Prisons and jails were not designed for public health emergencies and especially so in the case of airborne diseases. The prisons were built to keep many inmates as close as possible to give the guards an easier time monitoring them. While this is effective in preventing escapes and violence, these environments become Petri dishes for diseases like coronavirus.

In many prisons, inmates share facilities like sinks and toilets that are touched by multiple people, increasing the likelihood of spreading the virus. One correctional facility in Ohio, US, reported a nearly 80% COVID-19 infection rate.

Overcrowding in jails coupled with standard practices like pat-downs, cell shakedowns, and double (sometimes triple) bunking add to the challenge. Limited access to healthcare, sanitation, and personal protective equipment exasperates an already dire situation. The spaces are inflexible, making social distancing impossible.

Big residential blocks with large numbers of inmates and minimal ventilation only exacerbate the spread of COVID-19 prisons. Shared HVAC systems between units contribute to the spread of the disease.

One of the first things many institutions did was to restrict visitations and implement lockdowns. This has not proven effective in slowing down infection rates; instead, it only aggravates physical and mental conditions.

Adapting Prison architecture Post-pandemic

Prisons and jails were not designed for public health emergencies and especially so for airborne diseases. The prisons were built to keep many inmates as close as possible to give the guards an easy time monitoring them. While this is effective in preventing escapes and violence, these environments become Petri dishes for diseases like coronavirus.

In many prisons, inmates share facilities like sinks and toilets when these are touched by multiple people, the likelihood of spreading the virus increases.

Overcrowding in jails coupled with standard practices like pat-downs, cell shakedowns, and double (sometimes triple) bunking add to the challenge. Limited access to healthcare, sanitation, and personal protective equipment exasperates an already dire situation. The spaces are inflexible, making social distancing impossible. One of the first things many institutions did was restrict visitations and implement lockdowns. This has not proven effective in slowing down infection rates; instead, it only aggravates physical and mental conditions.

Pandemics and traumatic events shape our built environment, forcing us to learn and adapt our way of life.

Modalities of incarceration have shaped our level of acceptance of brutal prison architecture and have become desensitized to the plight of the incarcerated.

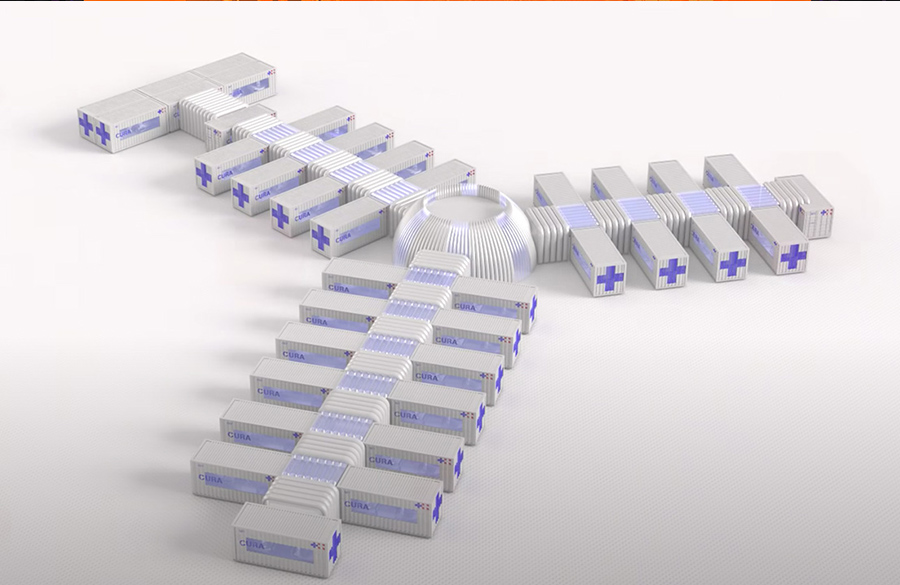

How then do we design for healing and pandemic preparedness and response?

Decarceration

Decarceration is the process of depopulating correctional institutions. Low-level crimes can be sent to rehabilitation centres instead of forcing them to start or continue their prison terms in the middle of a global health pandemic. This reduces pressure on the prisons and there’s less risk of spread of disease. When we view incarceration as an opportunity for rehabilitation and not punishment, we can build humane prisons.

Design for rehabilitation

The architecture of prisons defines what we expect out of the institution. This includes creating therapeutic spaces and calm environments for people to feel safe and secure. Design for healing, not for lockdown. Design for activities to support meditation, exercise, classes, and reading rooms. Coronavirus is an aerosolized disease, meaning it stays in the air and is inhaled by others, causing infection. airflow, therefore, is an important part of controlling the spread in prisons

Consider introducing softer and natural materials, including couches, area rugs, and products with natural finishes that evoke normalcy, comfort, and dignity.

Biophilia

The biophilic design encourages the use of natural systems and processes to allow for exposure to nature. Exposure to nature contributes to improved health and well-being on both physiological and psychological levels. (Gills, Soderlund).

Multiple studies have shown the importance of sunlight and natural ventilation for killing indoor infectious agents that cause airborne transmissions; they are effective in sterilizing and reducing infections in closed spaces (Dietz et al., 2020).

Reference:

- April 6, Michael MurphyUpdated, et al. “The Role of Architecture in Fighting a Pandemic – the Boston Globe.” BostonGlobe.com, www.bostonglobe.com/2020/04/06/opinion/role-architecture-fighting-pandemic/.

- Berg, Nate. “Bad Design Kills: Why COVID-19 Spread like Wildfire at One of America’s Worst Prisons.” Fast Company, 13 Aug. 2020, www.fastcompany.com/90539380/bad-design-kills-why-covid-19-spread-like-wildfire-at-one-of-americas-worst-prisons. Accessed 26 Apr. 2022.

- “How COVID-19 Could Impact the Design of Detention and Correctional Facilities.” HOK, 30 Apr. 2020, www.hok.com/news/2020-04/how-covid-19-could-impact-the-design-of-detention-and-correctional-facilities/. Accessed 26 Apr. 2022.

- kevin.town. “Promoting Safety and Rehabilitation in Prison during the Most Unusual of Years.” Www.unodc.org, www.unodc.org/dohadeclaration/en/news/2020/12/promoting-safety-and-rehabilitation-in-prison-during-the-most-unusual-of-years.html.

- McGuigan, Cathleen. “Designing for Decarceration in a Pandemic.” Architecturalrecord.com, Architectural Record, 27 May 2020, www.architecturalrecord.com/articles/14645-designing-for-decarceration-in-a-pandemic. Accessed 26 Apr. 2022.

- “Prison Design Creates Ideal Environment for Coronavirus.” WITF, 17 Apr. 2020, www.witf.org/2020/04/17/prison-design-creates-ideal-environment-for-coronavirus/.

- Slade, Rachael. “Is There Such a Thing as “Good” Prison Design?” Architectural Digest, Architectural Digest, 30 Apr. 2018, www.architecturaldigest.com/story/is-there-such-a-thing-as-good-prison-design.

- Wyatt, Dustin. “Architecture to Blame for COVID-19 Outbreak in Upstate Prison, State Officials Say.” Spartanburg Herald Journal, www.goupstate.com/story/news/coronavirus/2020/07/07/architecture-to-blame-for-covid-19-outbreak-in-upstate-prison-state-officials-say/41719709/. Accessed 26 Apr. 2022.

- Dietz, L., Horve, P., Coil, D., Fretz, M., …, & Wymelenberg, K. (2020). 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic: Built Environment Considerations To Reduce Transmission. Retrieved from American Society for Microbiology: https://msystems.asm.org/content/5/2/e00245-20