For much of its early years, crossing the English Channel was never an easy task. Traversing through the uneven waves on a boat/ferry in harsh chilly circumstances proved to be most difficult. Proposals for a smoother journey through the channel were looming as early as 1802. An initial idea of constructing a wide channel tunnel beneath the waters was first conceived by the French engineer Albert Mathieu Favier.

1. Design Planning and Solutions

He also visualized an artificial island midway for changing horses from the carriages drawn in. However, the plan and its progress fell through due to Britain’s fears of invasion from the French amidst the political tensions.

Rising to the challenge of linking the 2 countries, other early proposals varied from an extensive suspension bridge, a bridge-tunnel hybrid to a rail-road combo. Finally, in 1984, a joint agreement between the French and British governments called for a contest. This union would reduce pressure on just one country as the scale and scope of the project was too big to handle. The contest invited companies to submit their design proposal for the channel link and budget plans as this would be very expensive. This also included plans regarding the operation and lifecycle of the chunnel. The winning proposal amidst other tunnels/bridge proposals was submitted by the Balfour Beatty Construction Company due to a concrete design and expense plan. It was expected to cost $3.6 billion.

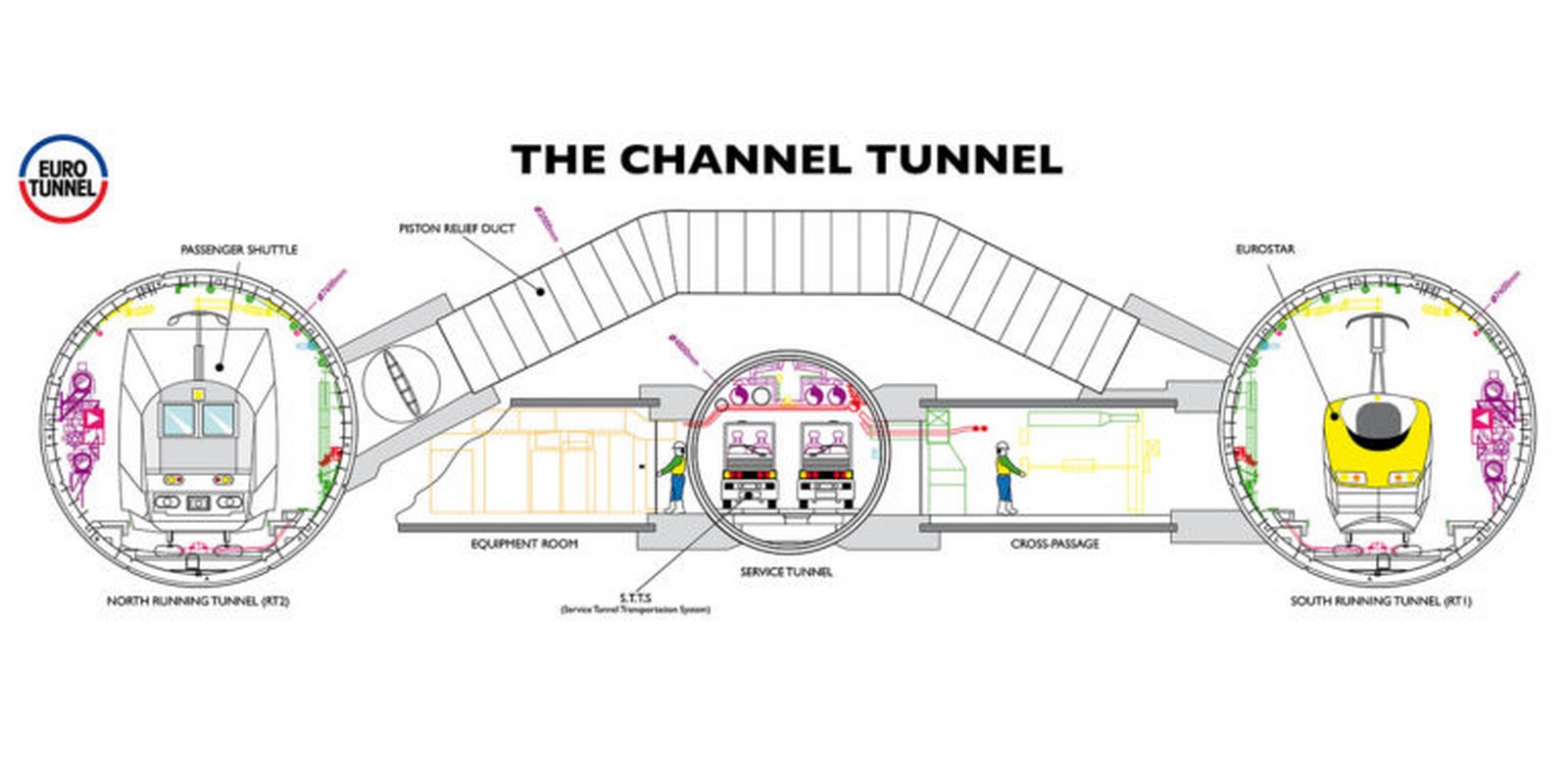

The design outlined an underwater tunnel below the Strait of Dover consisting of two parallel railway tunnels constructed with a smaller, third tunnel in between. This was meant for maintenance and operating services (drainage). The Channel Tunnel, also known as the Chunnel or Eurotunnel takes its course between Folkestone, England, and Sangatte, France. Each tunnel consists of a single track, a catenary above, and 2 walkways used for evacuation in case of accidents. At an interval of every 375 meters, a pair of cross passages connect the two tunnels to the central service tunnel enabling the train to switch to another track. This ensures a smooth stop at the station for maintenance or other emergencies in case the train needed a quick escape route. This allowed for train travel through both tunnels as well as the vehicular passage of cars/trucks reducing reliance and traffic on just one route. The train speed gets as high as 100 miles per hour with an average duration of 35 minutes.

2. Construction and Materials

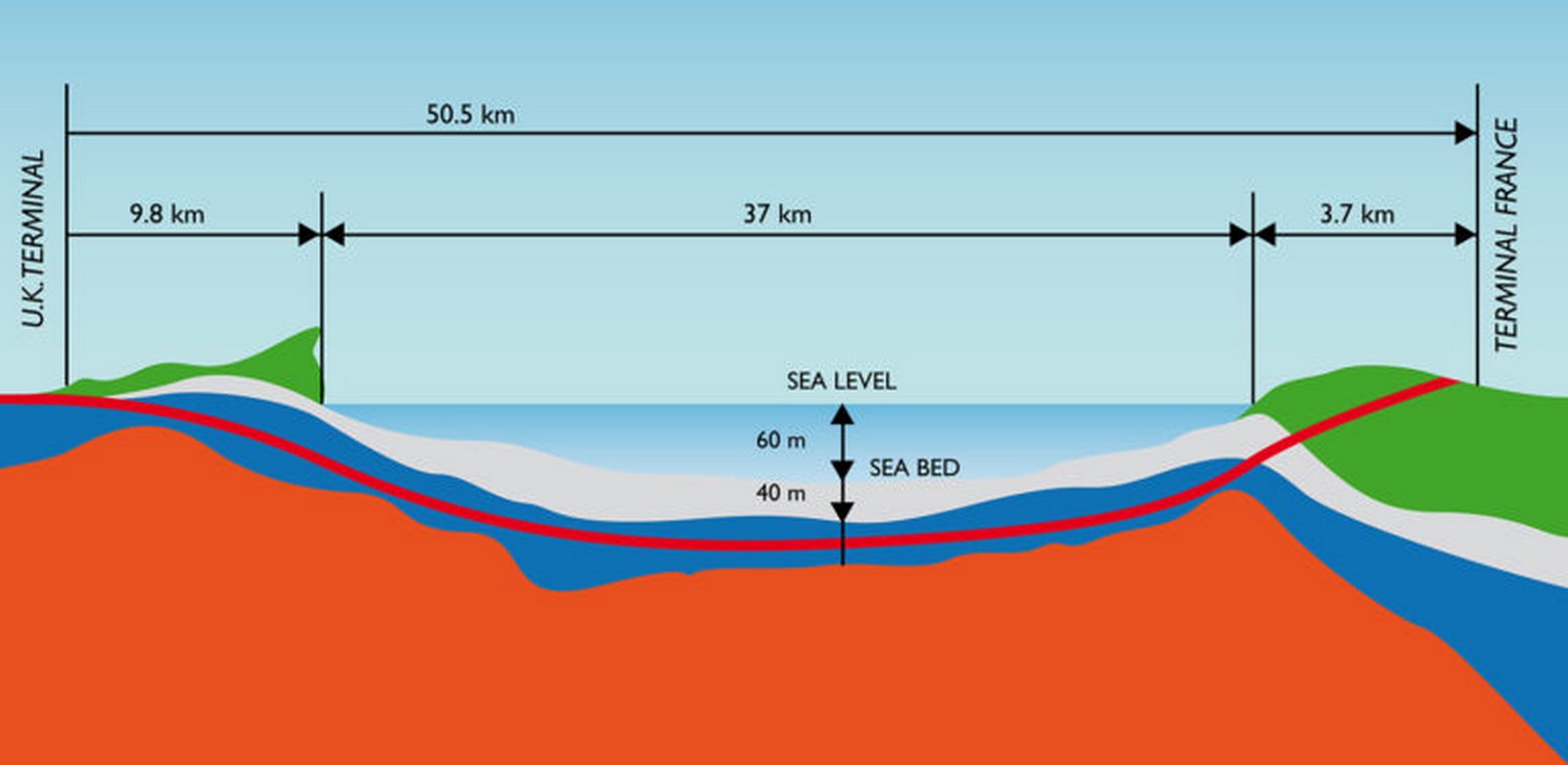

In an ambitious and most expensive effort to link France and England, a 2-inch diameter hole was drilled from both the respective coasts in hopes of meeting in the middle to form the finished tunnel. It would be the longest underwater tunnel in the world spanning over 50km (31 miles), making it a modern engineering marvel of the 20th century. Construction lasted 6 years beginning from 1988 with the British and French workers competing to reach the middle first, with the British taking the win. Nevertheless, history was made in the mere shared link and challenge won by the two.

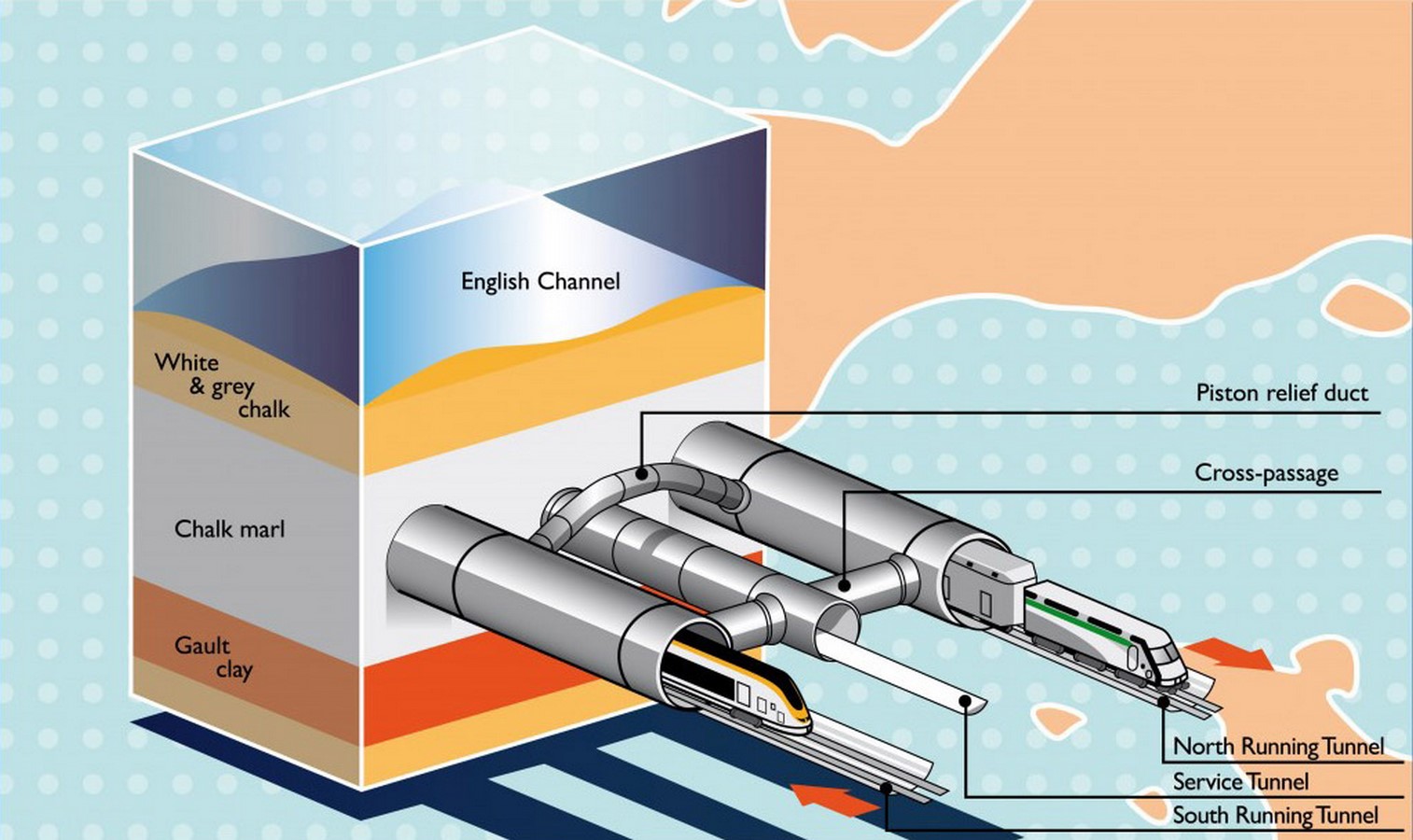

Digging under the mammoth-sized channel required a careful evaluation of its geologic condition. It was concluded that although there was a dense chalk layer on the bottom, the lower chalk marl layer was simple to cut through and is less susceptible to collapse. The laborious excavation was undertaken by 11 large tunnel boring machines (TBMs) weighing roughly 450 tonnes. Initially, the English side suffered a slight setback; the bored chalk layer was leaky, so grout was injected on the surface and their TBMs were waterproofed. This continued until they arrived at a less leaky part of the chalk layer.

As these machines with their rotating discs were bored into the chalk, the excavated rock debris moved along a conveyor belt towards the back. The average depth of the tunnel dug was 40m. The sides were coated with reinforced concrete to make it waterproof and durable to withstand the landlord. The lining was specially designed to last for 120 years. The French side used neoprene, grout sealed bolted linings made of cast iron or high-strength reinforced concrete whereas the English side used cast iron bolted linings for areas with weak stratum. Additionally, spheroidal graphite cast iron linings were applied in the connecting tunnels. This was followed by the application of precast tunnel lining segments along with the installation of services such as drainage pipes, ventilation ducts, lighting, power, etc.

Ensuring that the dug tunnel would merge in the middle from the British and French side was a testing venture that employed lasers and surveying equipment. Yet, the grand scale of the project did not guarantee such tools to give way to a reasonable result. Thankfully, on December 1, 1990, the shaking of hands from 2 workers on either side caused a frenzy of celebration at this historic achievement.

3. Sustainable Efforts

By its very nature, a completely underground transport system has an intrinsic environmental advantage of not emitting harmful gases on land. The CO2 emissions emitted while on a boat or ferry on the channel would have been 20 times more than simply traveling through the Chunnel. Compared to air travel, this is a more sustainable mode seeing as the journey from London to Paris emits 90% less greenhouse gas emissions than a flight, according to Eurostar. A study conducted in 2018 by JMJ Conseil stated that there has been a reduction in the emission of CO2 and greenhouse gases by 55% and an additional 20% by 2010. Further, to reduce exhaust emissions, 30 electric vehicles were used mainly in the service tunnel. By 2018, in hopes of raising the sustainability of the project, a new cooling system was installed delivering energy savings of at least 33 percent or 4.8GWh per year. This endeavor to maintain an optimal temperature inside combats the generated heat by high-speed trains which would normally increase the temperature to 35°C; now reduced to 25°C with the system in use.

The Eurotunnel continues to fulfill the charming travelogue of millions from London to Paris to Brussels. Connecting the island of Great Britain to the rest of Europe has shown to be a successful, political, financial, and tactful move.

References

- Rosenberg, J., 2019. The Remarkable Story Of How The Chunnel Was Built. [online] ThoughtCo. Available at: <https://www.thoughtco.com/the-channel-tunnel-1779429> [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- LetsBuild. 2015. How They Built The Channel Tunnel – Let’s Build. [online] Available at: <https://www.letsbuild.com/blog/how-they-built-the-channel-tunnel> [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- Smith, O., 2019. 25 Things You Might Not Have Known About The Channel Tunnel. [online] The Telegraph. Available at: <https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/france/articles/channel-tunnel-facts/> [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- Encyclopedia Britannica. 2019. Channel Tunnel | History & Facts. [online] Available at: <https://www.britannica.com/topic/Channel-Tunnel> [Accessed 15 July 2020].

- Railway Technology. 2020. Channel Tunnel, Strait Of Dover, the English Channel, UK/France. [online] Available at: <https://www.railway-technology.com/projects/channel-tunnel/> [Accessed 16 July 2020].

- WGBH Educational Foundation, 2000. Building The Channel Tunnel. Available at: <https://www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/phy03.sci.phys.mfw.bbchunnel/building-the-channel-tunnel/> [Accessed 16 July 2020].

- Atkinsglobal. 2014. Channel Tunnel: A Shared History. [online] Available at: <https://www.atkinsglobal.com/en-gb/angles/all-angles/channel-tunnel-a-shared-history> [Accessed 17 July 2020].

- Eurotunnel Le Shuttle Freight. 2020. Sustainable Development With Eurotunnel Le Shuttle Freight. [online] Available at: <https://www.eurotunnelfreight.com/uk/about/sustainable-development/> [Accessed 18 July 2020].

- PRNewswire. 2018. World’s Longest Undersea Tunnel Stays Cool And Reduces Environmental Impact. [online] Available at: <https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/worlds-longest-undersea-tunnel-stays-cool-and-reduces-environmental-impact-300656985.html> [Accessed 18 July 2020].

- Files.investis.com. 2003. Eurotunnel 2003 – Sustainable Development. [online] Available at: <http://files.investis.com/eurotunnel/en/sustainable_development.html> [Accessed 18 July 2020].