The 20th century witnessed a paradigm shift in architectural vocabulary with the emergence of Modernism. The world embraced functionality and minimalism. Functionality was reinforced through the rejection of ornaments and devotedly following the motto of form follows function. The minimalistic aesthetic gave rise to a form that was stripped of its unnecessary elements, which strengthened essentiality and practicality and was in tune with the technological advancements of society. But the radical change homogenized the urban fabric and slipped off its variety. The variety was due to the cultural differences of the place. The architectural vocabulary also dehumanized the spaces with little concern for the nuances of placemaking. When the creators of the modernist movement could envision the physical context, the cultural context was far more varied and complex, intangible and intriguing.

The Search for a Modern Indian Identity

Akin to how the tradition of a place evolves and gets adapted to the present context, the search for a modern Indian identity is a continuously evolving and ongoing process.

‘Our generation has been trying to discover the common thread in which the fabric of Indian Architecture has been woven in the past, and its significance for our times’ – Raj Rewal, 1984

The concept of modernity in India experienced different ideological shades. There was a need to redefine the architectural vocabulary of India post-independence. The Nehruvian ideology stemmed from the necessity to break free from the idea of ‘Raj’ and represent an architecture that represents progress, technological advancement, and liberalism in contrast to the Gandhian ideology which embraced the moral integrity of the villages and its small-scale industries. The different doctrines coexisted as architects and artists tried to bridge the gap by combining modernity with the essence of rural, vernacular architecture. This task was very crucial in the sense that the final built form should not be an overt reference to the imagery of a particular communal group or a mere facile imitation of a bygone era. Architects need to seek out the common thread that uplifts the culture of a place as well as respond to the technological advancements of society. Modern architecture in India has been undoubtedly shaped by the lifetime contributions of many architects, of which the works of Le-Corbusier, Charles Correa, and B V Doshi are pivotal.

Le Corbusier

Le Corbusier can be rightly called the father of Modern architecture in India. His works were seminal in defining the architectural vocabulary of Modern India though the situation during the time was of tension and ambiguity. In his iconic Assembly Building at Chandigarh, he uses different patterns such as the brise soleil grilles in varying scales and heights to create complex landscapes. Contrasting forms in concrete fuse together to define an architecture that reflected secularism with Indianness. Climate responsiveness was attained through prioritization of the slab and vault solutions for the roof to combat the heat, and the use of Indian elements such as brise soleil grilles, terraces, and tanks. The complex symbols of the natural ingredients let into the forms create imagery of Indianness. Overall his architecture inspired the future generation of architects to define Modernism with a flavor of India’s past.

Charles Correa

If Corbusier experimented with bold forms in concrete with a flavor of Indianness, Louis Khan crafted abstract geometries in brick. His iconic building, IIM Ahmedabad stands as a testament to his architectural ideologies. He conceived the institution as a mini city inspired by the essence of the Indian town through its climate responsiveness and placement of forms in different levels such as deeply shaded and breezy verandahs. The semi-open spaces took multi-functional roles and dramatically elevated the built form.

Charles Correa’s works were a perfect blend of the ideologies of Corbusier and Khan infused with the essence of the Indian vernacular. His seminal work, the Sabarmati Ashram at Ahmedabad has an amalgamation of brick piers, concrete beams, and low pavilions in a humanized scale aligning with the humble moral restraint of Gandhian ideology. The building was human in scale, adhering to the Gandhian ideology but at the same time rooted in traditions and climatically responsive. He also developed patterns of architectural vocabulary for warm humid and hot dry regions, climatically responsive solutions for transitional spaces, and passages connecting the public and the private realms which was significant in defining Modern architecture in India.

B V Doshi

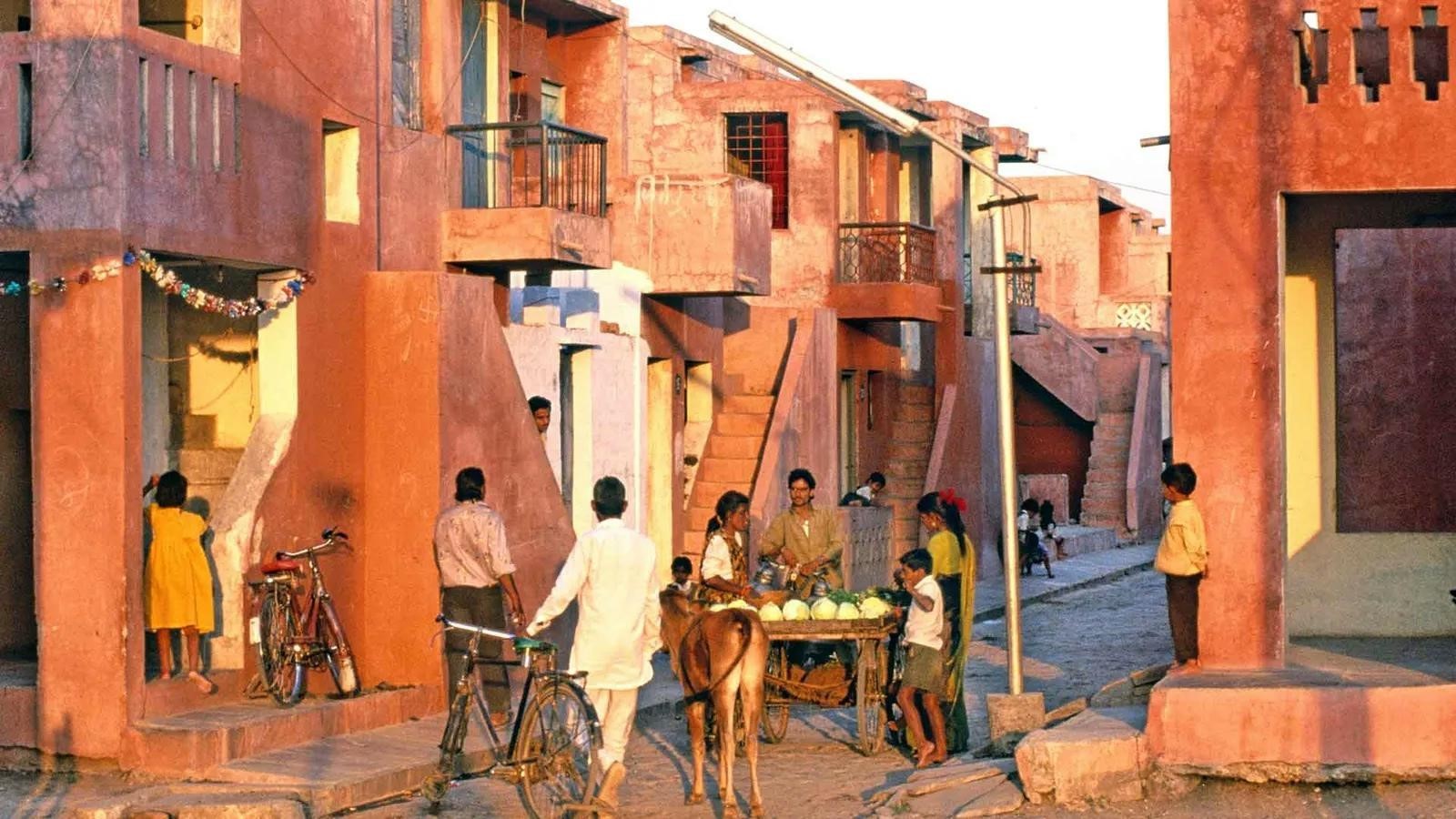

BV Doshi was pivotal in continuing the momentum of modern architecture. Instead of the brick and concrete vocabulary, a variety of local materials found its way into the built form which subdued the imagery of stark and bold concrete forms. As a response to the climate, natural climatic devices evolved to deal with the issues of heat, light, and ventilation. The spatial transitions became more seamless and the interiors blended with the outdoors through transitional spaces such as ledges, steps, and screens. The modern building was looked upon as a counterpart to the traditional city with streets, squares, gates, doorways, terraces, private courts, and platforms. His seminal work IIM Bangalore is a blend of the above patterns forming a new definition for Modern architecture. The Sangath in Ahmedabad, Aranya Low-Cost Housing in Indore, and the CEPT University, Ahmedabad are testaments to his ideologies which continue to inspire all those who look deep enough.

Conclusion

The patterns of modern architectural vocabulary are forever evolving through each architect’s work, adding a varied and newer dimension. It is noteworthy to mention the contributions of architect Laurie Baker and his contributions to society through his cost-effective construction methodologies and solutions. The modern has evolved to the contemporary with solutions to design problems that are far more varied and complex. India is a pluralistic nation and with the technological advancements, the future lies in developing a sustainable architectural vocabulary with patterns that are varied but at the same time sensitive and suitable to the context as well as to the evolving culture of the current times.

Reference

- Architectural Review (2016). Modernism and the search for Indian identity. [online]. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/places/india/modernism-and-the-search-for-indian-identity [Accessed date: 19 Aug 2023].

- Architectural Review (2016). Variations and traditions: the search for a modern Indian architecture. [online]. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/places/india/variations-and-traditions-the-search-for-a-modern-indian-architecture?utm_source=WordPress&utm_medium=Recommendation&utm_campaign=Recommended_Articles [Accessed date: 19 Aug 2023].

- Architectural Review (2016). A thoughtful synthesis of Western Modernism with what is essential in Indian traditional building. [online]. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/a-thoughtful-synthesis-of-western-modernism-with-what-is-essential-in-indian-traditional-building?utm_source=WordPress&utm_medium=Recommendation&utm_campaign=Recommended_Articles [Accessed date: 19 Aug 2023].

- Architectural Review (2011). The Assembly, Chandigarh. [online]. Available at: https://www.architectural-review.com/buildings/the-assembly-chandigarh [Accessed date: 19 Aug 2023].