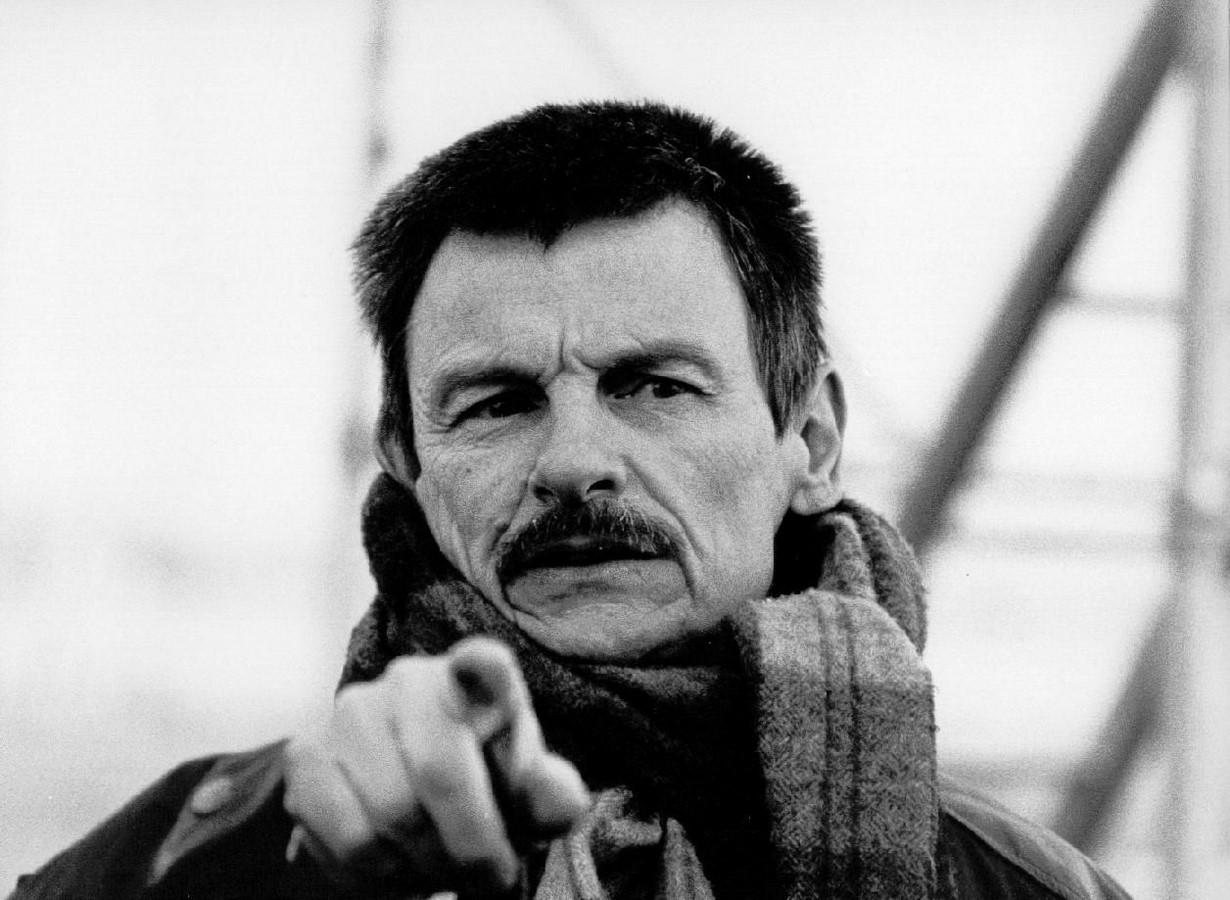

The pandemic has forever reshaped the relationship humans have with space. Houses were condensed into multifunctional spaces to accommodate recreation, living, and working leaving vast urban centers lifeless and eerie. But in this eeriness, there was solace, a dystopic beauty that helped one appreciate those communal built forms even more through their absence. The renowned Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky captured this architectural eeriness in beautifully dystopic frames thirty years before the pandemic. His goal in all his films was to allow the viewer to experience familiar spaces through alien eyes by taking out the conventional beauty that one often associates with an aesthetic frame.

Dingy rooms, uncleaned broken windows, wet floors, leaking roofs, broken walls, and a general sense of uncomfortableness are common elements and themes found in Tarkovsky’s films. Through understanding darkness, efficient use of perspectives, delicately crafted color schemes, and setting the subjects up in the right manner, Tarkovsky showcased these lifeless environments gracefully. He set his environments up in wide frames that lasted for an unconventionally long duration of time allowing the viewers to absorb every detail. Often in films, the primary subjects of a frame are the actors. While the actors are still the primary focus, the majority of Tarkovsky’s frames emphasize the environments around them with the actors lingering and breathing life into an eerie still frame.

Time and structure.

The concept of time was a fil rouge in every Tarkovsky film both for the subjects involved and the viewer. One does not come out of a Tarkovsky film with the same perspective on time. Often a single frame with a broken building or landscape would last for several minutes involving minimal activities. When asked, Tarkovsky often said that cinema is the only art form that can fix reality by controlling and fixing time through drawn-out frames. Architecture facilitates creating a mosaic made with time in his films. The powerful and sometimes overwhelming nature of the structures present in Tarkovsky’s films showcases a harsh reality that engages the viewer in a visual dialogue.

Architectural elements such as broken furniture, creaking doors, and empty swimming pools are parts of the built environment that are objectively considered disturbing. Tarkovsky utilized these elements in drawn-out frames to allow the viewer to patiently take in these details. The main actors were just mere elements in Tarkovsky’s environment showcasing an architectural relationship often not seen in cinema. His environments, both built and natural, enabled the dialogues in his films with minimal human conversations involved. These dialogues showcased the outcomes of greed and exploitation in a human-centric world. One can also see several natural elements such as creepers, tall grass, sand, and trees present in between the built forms indicating hope crawling out from the rubble. Tarkovsky’s understanding of architecture in its raw state is seen in all his films.

Architecture facilitates Tarkovsky’s trance-inducing frames.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s films have a dream-like quality to them where viewers experience familiar reality as foreign. Simple aspects of his cinematography are often trance-inducing as he utilizes architecture to instigate these emotions. For example, footsteps on glass or water-filled floors are pacemakers imitating a clock that locks our attention on time. Tarkovsky ensures to highlight and increase the volume of these pacemakers and his surrounding environments in general allowing the viewers to feel every second of a shot. This is especially seen in his film “Stalker” which has several scenes with water-filled broken-down structures and environments. By setting up this simple aspect of his cinematography, Tarkovsky ensures that the viewers appreciate the beauty present in a dystopic architectural setting.

Another aspect of Tarkovsky’s architectural cinematography involves efficiently setting up perspectives for a scene. He would emphasize and prioritize the surroundings and the built environment to set up frames that allow architecture to facilitate dialogue. Often the camera would move back and forth on a subject walking through space mimicking a pendulum. Mist, rain, fire, and other natural elements were utilized to highlight the depth of space. Tarkovsky experimented with darkness and light, enabling shadows to build his worlds and define the scenes he created. These perspectives dilute a segment of the viewer’s timeline to such a degree that Tarkovsky makes one experience a glimpse of infinity present in the normal rhythms of life through his distinctive cinematography.

Existentialism through architecture.

Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinematography is a result of his profound exploration of niche themes involving spirituality, existentialism, and philosophy that were reflected in all his films. Stalker, Solaris, Mirror, The Sacrifice, and many more of his films were powerful not only in terms of the meaning the films carried but also in the powerful display of architecture that aided the existential themes of his films. Tarkovsky understood the many possible layered dialogues that the built environment can have with the users. His understanding of materiality, lighting, acoustics, and scale made him a distinct voice in the world of cinema wherein he enabled viewers to put themselves as users of the spaces and environments that he depicted in his films. One could argue that Tarkovsky’s architectural understanding could rival many practicing architects of his time.

Tarkovsky’s films celebrate dystopic and broken-down architecture. His understanding of space, the built, and the unbuilt merged into creating architecturally visual cinematic masterpieces that hold their own four decades later. His spaces and environments were layered meaningfully representing the fixation of time, the nature of spirituality, destructive reflections of humanity, and the life that is taken for granted. In a world where cinema depicts the objective beauty of architecture, Tarkovsky stands out as a filmmaker that depicted the worn-down eerie nature of architecture as a beautiful dystopia.

References.

Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.). Andrey Arsenyevich Tarkovsky | Soviet film director. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Andrey-Arsenyevich-Tarkovsky.

Ross, A. (2021). The Drenching Richness of Andrei Tarkovsky. [online] The New Yorker. Available at: https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2021/02/15/the-drenching-richness-of-andrei-tarkovsky.

the Guardian. (n.d.). Andrei Tarkovsky | Film | The Guardian. [online] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/andrei-tarkovsky.

offscreen.com. (n.d.). The Spiritual Cinema of Andrei Tarkovsky. [online] Available at: https://offscreen.com/view/spiritual_cinema_tarkovsky.

Cain, M.L. (n.d.). Tarkovsky, Andrei – Senses of Cinema. [online] Available at: https://www.sensesofcinema.com/2002/great-directors/tarkovsky/.

Le Fanu, M. (2017). Stalker: Meaning and Making. [online] The Criterion Collection. Available at: https://www.criterion.com/current/posts/4739-stalker-meaning-and-making.