Expressions of identity in architecture could be assessed by their continuity in depicting core cultural values, distinctions in tackling local or regional challenges, along with the recognition of elements that consolidate and distinguish one cultural group from another. [1]

The issue essentially lies in creating a built environment shaped by and wholly belonging to its context through visual and experiential mediums. Thus, it requires the recognition and creative transformation of values accumulated over centuries in combination with newer, more alien ones[2] – containing genuine impressions of cultural heritage while satisfying the technological, environmental, and functional needs of contemporary users.

The task of forging an identity in modern Middle eastern architecture entails embracing paradoxical notions of projecting specific cultural images while simultaneously meeting the needs of the present.[3] However, the homogenization of globalism and reactionary nationalist sentiments have forever changed the region’s urban landscape, yielding mixed results.

Most modern Middle Eastern architecture either eschews tradition or solely focuses on the superficial layering of traditional elements like domes, mashrabiya, arches, screens, windcatchers, and geometrical patterns, to project contrived notions of the visual dimension of identity. [4]

Modernism and postmodernism were not analyzed for their faults after their import in the mid-20th century but tacitly accepted. [5] Moreover, top-down decision-making approaches have alienated residents and facilitated gentrification while prioritizing corporate or political interests.

Developmental models within modern Middle Eastern architecture could be categorized under two grand narratives, as elucidated by the architect and historian Mohammad Al-Assad. [6] The first category involves the oil-rich countries of the Arabian Gulf while the latter comprises low and middle-income countries of the Middle East, encumbered by recent economic stagnation or civil unrest.

The exorbitant wealth pouring into the states surrounding the Arabian Gulf after the discovery of oil was the catalyst for its frenzied modernization at the turn of the millennium. Coastlines adjacent to barren deserts previously populated by pearl divers, fishermen, and Bedouin nomads—lacking the infrastructure that birthed Western industrialization, [7] were transformed into continuous high-density urban hubs of trade, finance, and tourism in half a century. Urbanization emerged from requirements for housing, infrastructure, commercial, and office spaces for an inward flood of expatriate workers. [8]

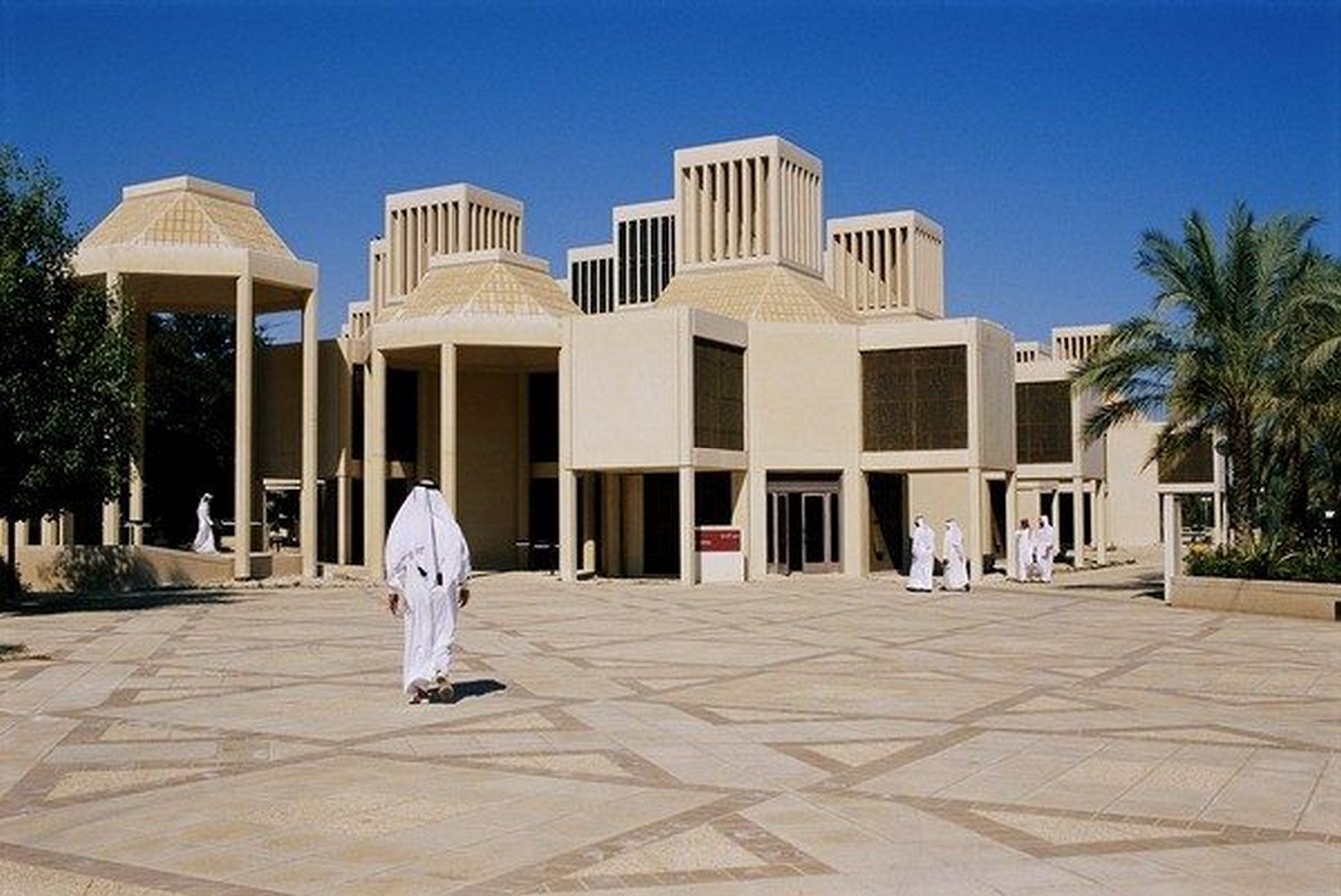

Narrow, winding streets between indigenous buildings that dealt with hot, unforgiving climates in the Medinas of yore [9] gave way to multi-laned highways, flyovers, grids, skyscrapers, and concrete pavers. Following early attempts to forge identity like the Qatar University Campus, Western development encompassed all visions of modern lifestyles—despite creating a false identity attuned to a different context [10] and climate, with little sense of the human scale.

Moreover, while their cities altered appearances and societies grew more liberal, the core cultural conservatism of these countries remained at odds with the globalist viewpoints they portrayed through architecture. Rulers have attempted to boost local economies by emulating the Bilbao effect, [11] most evidently in Dubai—which spiralled into a competition for icons[12] , attracting foreign architects to compete for the massive commissions involved.

This image building exercise yielded a plethora of architectural marvels including the Burj Khalifa, Louvre Abu Dhabi, Qatar National Library, Kuwait’s NBK building, Saudi Arabia’s Kingdom Centre, and Bahrain’s World Trade Centre.

While these buildings and the Dubai model are astonishing achievements of technical ingenuity, their contextual responsiveness and socio-economic inclusivity are dubious. These concerns could extend to most modern Middle Eastern architecture built by professionals trained exclusively in modernist schools, who relied on historical justifications to transform the region with forms and materials taken from another part of the world [13] — projecting opulence but lacking character.

The UAE’s skylines are littered with crude imitations of western skyscrapers for this very reason. The dominance of imported building methods within the Middle East as a whole betrays a lack of faith in indigenous traditions now associated with poverty. [14]

Under the second narrative, mid-20th-century Egypt experienced historic revivalism in buildings such as its Supreme Court, vernacular architecture championed by Hassan Fathy, and modern regionalism exemplified by the Nile Art Gallery or Gamal Bakry’s Cairo Commercial and Tourist Centre. [15] Privatization and economic reforms eventually bred cities with a neoliberal character employing postmodernism through traditional ornamentation on commercial facades like the Faisal Bank of Cairo and the Headquarters of the Oriental Weavers. [16]

Iran initially embraced modernism under the Shah but tempered it with elements derived from indigenous traditions [17] — evident in projects such as the Azadi Tower, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Shushtar New Town Housing Complex. The revolution of 1979 and its rejection of Western influence lead to the increased incorporation of local elements, [18] particularly in the postmodern vein as seen in the Milad Tower and Al Ghadir Mosque.

Shanty towns and high rises came up to handle overcrowding, pollution, water shortages, and binary class geographies in Tehran. At present, the city’s veneer of austerity and repression hides a bustling cosmopolitanism underneath.

Cities like Cairo and Beirut were emblems of cutting edge urbanism in the Arab world before the oil boom, [19] but their approaches were subsequently shunted aside for the Dubai model due to its propensity for tourism and revenue generation. Beirut’s SOLIDERE initiative, touted as an urban renewal project after its devastating civil war, epitomized this shift.

Despite including elements of conservation, it was inherently a starchitect-driven real estate development that infringed upon property rights, reinforced exclusionary economic hierarchies, and either blindly implemented contemporary trends or created pastiche cultural representations. [20]

The old city of Sana’a in Yemen—a World Heritage Site—represents an interesting foil to these cases where conservation occurred in tandem with modernization. Certain traditional practices did not die out but were adapted to modern needs, although their implementations, functionality, and aesthetic value are debatable.

For instance, the city’s iconic tower houses—once paragons of communal living, have now grown in height to appropriate the style of multi-storey apartment blocks. Concrete construction, despite its poor climatic performance, replaced masonry walls as brickwork became purely ornamental. [21] Worse still, the country’s recent civil war hindered the continuation of this valued tradition and laid waste to its cities.

As evident from these cases, population growth, civil unrest, and wealth inequality coupled with overbuilding, urban decomposition, and the influx of profit-centric neoliberal ideas have challenged experimentation in forging a contextually sensitive yet contemporary way of building. Unfortunately, this is a common thread in developing nations.

Residents, rulers, planners, and architects in the region must question whether modern Middle Eastern architecture genuinely reflects their values, aspirations, and heritage. The concept of identity has always been fluid and ever-changing with the cultural zeitgeist, which is particularly true for this region, where significant advances have occurred within a short time-frame.

The incoherence and inequality borne of current models indicate that careful consideration and deliberation over the region’s built heritage and the underlying social practices that define it are essential to rectify the purely cosmetic angles that presently define synthesis of the old and new. Greater public participation is also vital to encourage more personal investment and input from residents in the moulding of their urban surroundings.

The goal is not to formulate a recipe or one-size-fits-all solution, but rather to develop analytical frameworks and encourage critical discussions on the issue of place-making within the ephemerality of the modern built environment.

References

- Tarek Abdelsalam (2009) A Comprehensive Framework for Approaching the Architectural Identity Dilemma in the Design Studio, May 2009 Architectural Education Forum 4: Flexibility in Architectural Education [1]

- Mahmoud Abedi & Hosein Soltanzadeh (2014) The Interaction between Tradition and Modernity in Contemporary Architecture of Persian Gulf States: Case Study of United Arab Emirates, International Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Studies Volume 1, Issue 1, November 2014, pp 24-34 [2] [14]

- Salama, A. M. (2005). Architectural Identity in the Middle East: Hidden Assumptions and Philosophical Perspectives. In D. Mazzoleni et al (eds.), Shores of the Mediterranean: Architecture as Language of Peace. Intra Moenia, Napoli, Italy pp. 77-85 [3] [5] [10]

- Salma Samar Damluji (2006) The Architecture Of The United Arab Emirates [4] [7] [8]

- Mohammad al-Asad (2008) The Contemporary Built Environment in the Arab Middle East, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 25-27 [6]

- Joseph J. Hobbs (2017) Heritage In The Lived Environment Of The United Arab Emirates And The Gulf Region, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research, Volume 11, Issue 2 , July 2017, pp. 55-82 [9]

- Nicolai Ourousoff (2010) Building Museums, And A Fresh Arab Identity, New York Times, Web [11]

- Kevin Mitchell (2008) Dubai: Selling a Past to Finance the Future? Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp 49-51 [12]

- Marwa Al-Sabouni (2016) Architecture with Identity Crisis: The Lost Heritage of the Middle East, Journal of Biourbanism Volume 1&2/2016 pp. 81–97 [13]

- Ashraf M. Salama (2008) Cairo’s Plurality of Architectural Trends and the Continuous Search for Identity, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 13-15 [15]

- Nasser Rabbat (2008) Egypt: Modernity and Identity, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 16-18 [16]

- Mohammad Gharipour (2009) Tradition versus Modernity: The Challenge of Identity in Contemporary Islamic Architecture, PhD Morgan State University [17]

- Mina Marefat (2008) Modernizing and De-Modernizing: Notes on Tehran, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 52-56 [18]

- Rami Daher (2008) Global Capital, Urban Regeneration, and Heritage Conservation in the Levant, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 22-24 [19]

- Oliver Wainwright (2009) Is Beirut’s Glitzy Downtown Redevelopment All That It Seems, The Guardian, Web [20]

- Michele Lamprakos (2008) Old Heritage, New Heritage: Building in Sana‘a, Yemen, Viewpoints Special Edition: Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East, pp. 33-36 [21]