Introduction

The relationship between architecture and place is a multifaceted and profound connection that has existed for centuries. It is a topic of great significance within the fields of architecture, urban planning, and environmental design (Rapoport, 1990). Architecture, as both a practical and artistic discipline, has the power to influence and shape the character, identity, and functionality of a specific location or environment. In this comprehensive exploration, we will delve into the intricate and dynamic interplay between architecture and place, examining how architecture responds to its context, expresses cultural identity, considers environmental factors, meets functional needs, fosters social interaction, contributes to a sense of place, influences urban planning, and plays a role in preservation and conservation.

Contextual Sensitivity

Architecture’s relationship with place begins with contextual sensitivity. Every location, including India, has a unique set of physical, cultural, historical, and environmental attributes that define its character and essence. Architects must be acutely attuned to these contextual factors when designing buildings and structures. Contextual sensitivity involves the harmonious integration of a new architectural intervention within its surroundings, whether it is situated in a rural landscape, an urban centre, or a historic district.

In India, a prime example of contextual sensitivity is the Lotus Temple in New Delhi. Designed by Iranian architect Fariborz Sahba, this Bahá’í House of Worship blends seamlessly with its surroundings, resembling a lotus flower in full bloom. The use of white marble complements the city’s architectural palette while symbolizing purity and divinity. The Lotus Temple not only respects the cultural context but also creates a serene and contemplative space within a bustling urban environment.

Cultural Identity

The cultural identity of a place is profoundly influenced by its architecture, and India offers a rich tapestry of architectural diversity. Different regions and communities possess distinct architectural traditions, styles, and aesthetics that reflect their cultural values, history, and heritage. Architecture serves as a visual and tangible representation of these cultural identities, leaving an indelible mark on the character of a place (Ching & Binggeli, 2014).

In India, the Jaipur City Palace stands as a testament to the fusion of Rajput and Mughal architectural styles. Constructed in the 18th century, this palace complex showcases intricate marble work,

colourful frescoes, and ornate courtyards. It exemplifies the cultural identity of Rajasthan, where vibrant artistry and regal heritage are deeply embedded in the architecture.

Furthermore, architecture plays a pivotal role in the preservation and celebration of cultural heritage in India. Historic buildings like the Taj Mahal and Hawa Mahal in Jaipur serve as enduring symbols of the country’s architectural prowess and cultural heritage (Ching & Binggeli, 2014). These iconic structures attract visitors from around the world, fostering an appreciation for India’s rich history.

In contemporary Indian architecture, architects often engage in a dialogue with the country’s diverse cultural identity. They may incorporate elements from the past into modern designs or reinterpret traditional architectural forms in innovative ways. For instance, the Indian Institute of Management (IIM) in Ahmedabad, designed by Louis Kahn, incorporates elements of Indian step-wells into its architecture, blending modernity with a sense of cultural continuity.

Environmental Considerations

The relationship between architecture and place extends to environmental considerations in India, a country with diverse climates and landscapes. Sustainable architecture, also known as green or ecological architecture, has gained prominence in addressing environmental concerns and respecting India’s unique ecosystems (Pallasmaa, 2014).

In regions like Kerala, where heavy monsoon rains are common, architects incorporate sloping roofs, wide eaves, and rainwater harvesting systems to manage water efficiently. The traditional Kerala house, known as the “Nalukettu,” is a prime example of architecture that responds to local environmental conditions. It features a central open courtyard for natural ventilation and light, promoting comfortable living even in a humid climate.

Moreover, the revival of traditional Indian building techniques, such as mud architecture and bamboo construction, demonstrates a commitment to sustainability. These materials are readily available and eco-friendly, making them ideal for creating buildings that are in harmony with the environment.

Indian architecture also embraces the principles of Vaastu Shastra, an ancient architectural philosophy that considers the orientation of buildings in relation to natural elements and cosmic energies. By aligning structures with the cardinal directions and adhering to Vaastu principles, architects aim to create living spaces that are in harmony with the natural world.

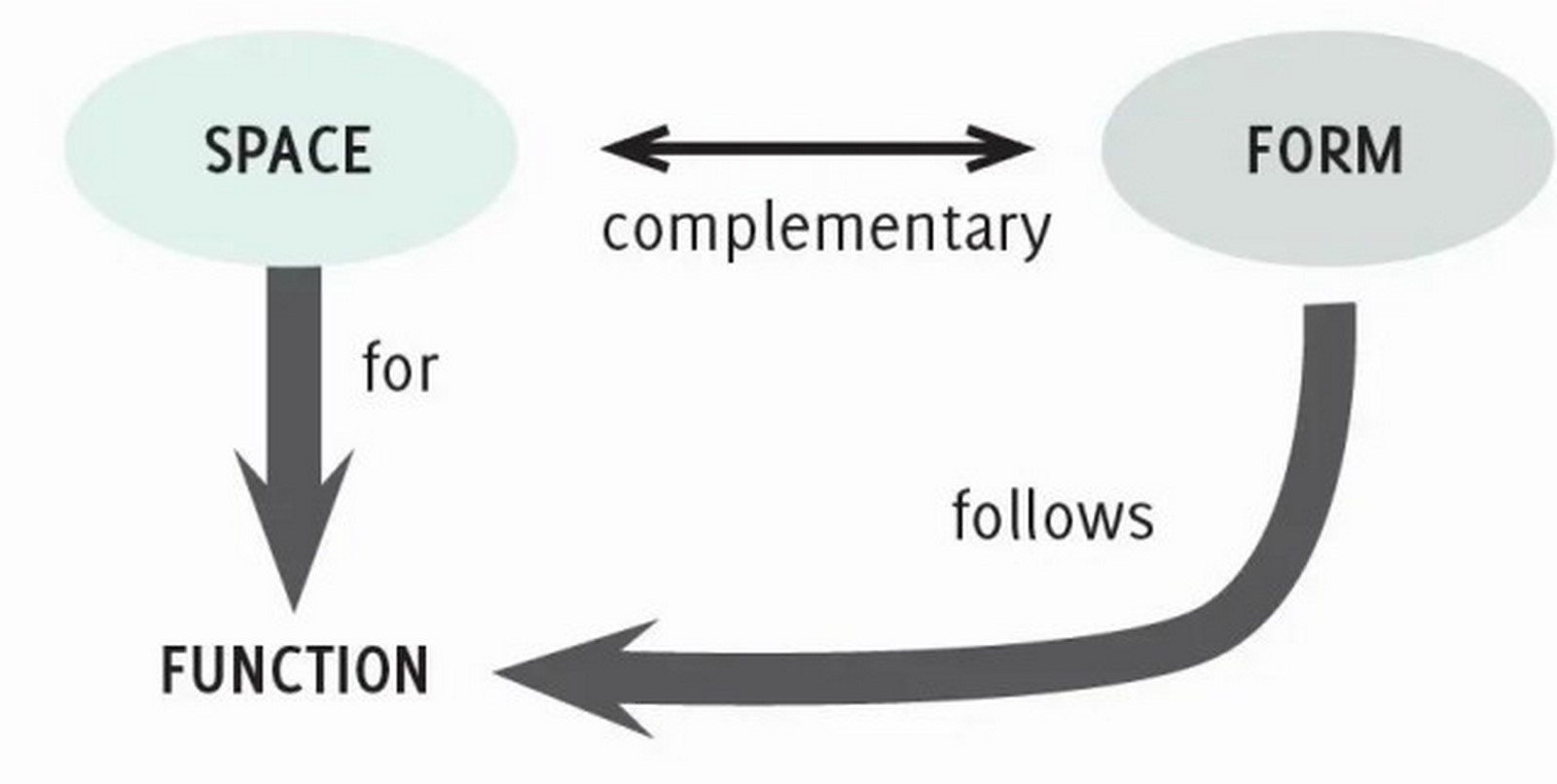

Functional Adaptation

Functionality is a fundamental aspect of architecture’s relationship with place in India, a country with diverse and evolving needs. Buildings must meet the functional needs of a place and its inhabitants, whether it is a residence, a commercial area, an educational institution, or a public space. Architects work closely with clients and stakeholders to understand the specific requirements of a project and translate them into a functional and efficient design (Ching & Binggeli, 2014).

In the realm of public infrastructure, India’s metro rail systems exemplify functional adaptation to urban needs. Cities like Delhi, Bengaluru, and Mumbai have invested in modern metro networks that alleviate congestion, reduce pollution, and enhance urban mobility. These systems provide efficient transportation options while considering the high population density of urban areas.

In public spaces, such as Ahmedabad’s Sabarmati Riverfront, architects consider the needs of diverse user groups. The riverfront project transformed a neglected area into a vibrant public space with pedestrian promenades, gardens, and cultural venues. The design prioritizes inclusivity and encourages social interaction, offering residents and visitors a respite from the city’s hustle and bustle

Social Interaction

Architecture has a profound influence on social interaction within a place, and India’s diverse communities and traditions underscore the importance of well-designed public spaces. Well-designed buildings and public spaces can encourage people to gather, engage with their surroundings, and interact with one another.

India’s historic palaces, forts, and temples have long served as gathering places for cultural and religious activities. The sprawling courtyards and intricate architecture of places like the Amber Fort in Jaipur provide settings for festivals, ceremonies, and social gatherings. These spaces foster a sense of community and cultural identity (Whyte, 1980).

In contemporary India, urban plazas and cultural centres continue to play a vital role in promoting social interaction. For example, the Bengaluru Art Park hosts exhibitions, performances, and workshops, creating opportunities for people to engage with art and one another. Such spaces contribute to the social fabric of cities and enhance the quality of urban life (Gehl, 2010).

Sense of Place

A sense of place in India refers to the unique character and emotional connection that people have with a particular location. It is an intangible quality that is deeply rooted in the physical, cultural, and social aspects of a place. Architecture plays a pivotal role in shaping and enhancing the sense of place, making it a central concern in the design and planning of environments (Whyte, 1980).

Indian architecture’s ability to evoke a sense of place is exemplified by the Udaipur City Palace in Rajasthan. This sprawling palace complex overlooks Lake Pichola and combines Rajput and Mughal architectural styles. Its intricate details, vibrant colours, and panoramic views create an unforgettable experience for visitors, allowing them to connect with the rich history and natural beauty of Udaipur.

In the realm of residential architecture, traditional courtyard houses, or “Havelis,” are celebrated for their ability to foster a sense of community and privacy simultaneously. These homes feature central courtyards that provide a private oasis while connecting inhabitants to the outdoors. The courtyard becomes a place for family gatherings, celebrations, and daily life, strengthening the bond between architecture and the sense of place.

Influences on Urban Planning

Architecture’s impact extends beyond individual buildings to influence urban planning and city development in India. Well-designed and thoughtful architectural interventions can set the tone for urban revitalization and contribute to the overall quality of urban life (Gehl, 2010).

In India’s capital, New Delhi, the Connaught Place redevelopment project exemplifies how architectural interventions can transform a city centre. The restoration of this historic commercial hub involved preserving its colonial-era architecture while enhancing its functionality and accessibility. The revitalized Connaught Place has become a thriving urban destination, attracting businesses, shoppers, and tourists alike.

Additionally, architecture plays a role in addressing pressing urban challenges in India, such as housing affordability and sustainability. Architects and urban planners collaborate to design sustainable housing solutions, transit-oriented developments, and eco-friendly infrastructure. These initiatives aim to create more livable, walkable, and environmentally responsible cities that meet the needs of India’s growing urban population (Thomaier et al., 2010).

Preservation and Conservation

Preservation and conservation are vital aspects of architecture’s relationship with place in India, a country with a rich history and architectural heritage. Historic preservation efforts seek to protect and maintain buildings and landmarks of historical, cultural, or architectural significance, ensuring that the built heritage of a place is preserved for future generations (Whyte, 1980).

India’s efforts to preserve its architectural heritage are evident in the restoration of structures like the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus in Mumbai. This iconic railway station, designed by Frederick William Stevens, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The meticulous restoration work preserves the station’s Gothic Revival architecture and intricate ornamentation, allowing it to continue serving as a functional transportation hub and a testament to India’s architectural legacy.

Conservation principles in India also extend to natural environments. Architectural designs consider the preservation of fragile ecosystems, biodiversity, and cultural landscapes. Initiatives like the restoration of the Sunderbans mangrove forest showcase how architecture can support conservation efforts by minimizing its impact on the surrounding environment.

Conclusion

The relationship between architecture and place in India is a dynamic interplay of tradition, innovation, cultural diversity, and environmental sensitivity. Architects in India, like their counterparts worldwide, face the challenge of creating spaces that respond to the unique characteristics and needs of each location (Rapoport, 1990). By embracing the principles of contextual sensitivity, cultural identity, sustainability, functionality, and social interaction, architecture continues to enhance the quality of India’s built environment and strengthen the profound relationship between architecture and place.

In a country known for its architectural marvels, from ancient temples to modern skyscrapers, the impact of architecture on India’s cultural and physical landscape is undeniable. As India continues to evolve and urbanize, architects and urban planners have a crucial role to play in shaping cities and communities that are not only functional but also culturally rich, environmentally sustainable, and socially inclusive. Through thoughtful design and a deep understanding of place, architecture in India continues to celebrate the nation’s diversity and heritage while embracing the challenges of the future.

References:

Rapoport, A. (1990). History and Precedent in Environmental Design. Plenum Press.

Ching, F. D. K., & Binggeli, C. (2014). Interior Design Illustrated. Wiley.

Pallasmaa, J. (2014). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. Wiley.

Thomaier, S., Haase, D., Köpnick, J., & Bonn, A. (2010). How to Use Space Syntax in Urban Analysis: What Is the Evidence of Consistency in the Effects of Land Use Mix on Walking and Cycling? Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 37(6), 983-997.

Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for People. Island Press.

Whyte, W. H. (1980). The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. Project for Public Spaces.

Steemit. (n.d.). Steemit. William H. Whyte & The way we understand our public spaces — https://steemit.com/design/@mintvilla/william-h-whyte-and-the-way-we-understand-our-public-spaces